Quick quiz: What did the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s and 2010s all have in common?

Not a lot, perhaps, but in each of those decades, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority always seemed just one or two steps away from fiscal disaster, with regional leaders warning of dire consequences up to and including a “death spiral” for the regional transit system.

The 2020s are only three years old, and while the singers come and go, the song remains the same.

Even pro-transit local leaders, which would be most of them, acknowledge that drastic and well-publicized cuts to the system to fill a projected $750 million operating-fund gap in the coming year are merely saber-rattling.

“If you get to those level of cuts, you might as well just shut down the system and call it a day,” said Arlington County Board Chairman Christian Dorsey, who at a July 18 meeting said it was incumbent on regional leaders to work toward a transit system that is “re-thought and right-sized.”

“We’ve really got to figure out what our ‘new normal’ is in terms of [post-pandemic] commuter patterns. Metro needs to be able to be relevant to that new normal,” the board chair said.

Arlington’s share of addressing a $750 million regional shortfall would be about $60 million on top of what the community already provides in transit subsidies.

“It’s inconceivable,” Dorsey said. “It is fiscally not possible.”

Perhaps unconsciously, Dorsey hit upon a theme some voices in the wilderness were whispering at the very start of the pandemic in 2020: If you allow people to get comfortable working from home, they’re never going to want to come back to the office, and that would have broader ramifications not just for the Metro system specifically, but for the economies of office-building-heavy communities such as Arlington.

Local-government leaders, who were quick to shut down their own in-person operations in March 2020 and somewhat slow to get them back up and running, seem to be connecting the dots between those types of actions and their ramifications.

“We need people to fill the trains. We’ve got to get workers back on trains going to offices,” said Dorsey, using the word “skittishness” to describe the current attitude of both employees and employers.

(The board chair also ripped into the federal government for not providing more support for the Metro system. “I had to get a few things to get off my chest,” Dorsey said in concluding his remarks.)

Again echoing a theme that just as easily could have come up in any decade since the regional compact that created the Metro system and its Byzantine financing and governance regimes came into effect in the 1960s, County Board member Takis Karantonis said the time has come to develop permanent solutions.

"The stakes are really very, very high,” he said. “We are at a real point of reflexion.”

When the transit system came into operation in the 1970s, there was a wide disparity in views about its importance to the region – officials in Loudoun County long avoided being drawn in, and Fairfax officials frequently made threats – usually idle but sometime carried through – to hold back funding.

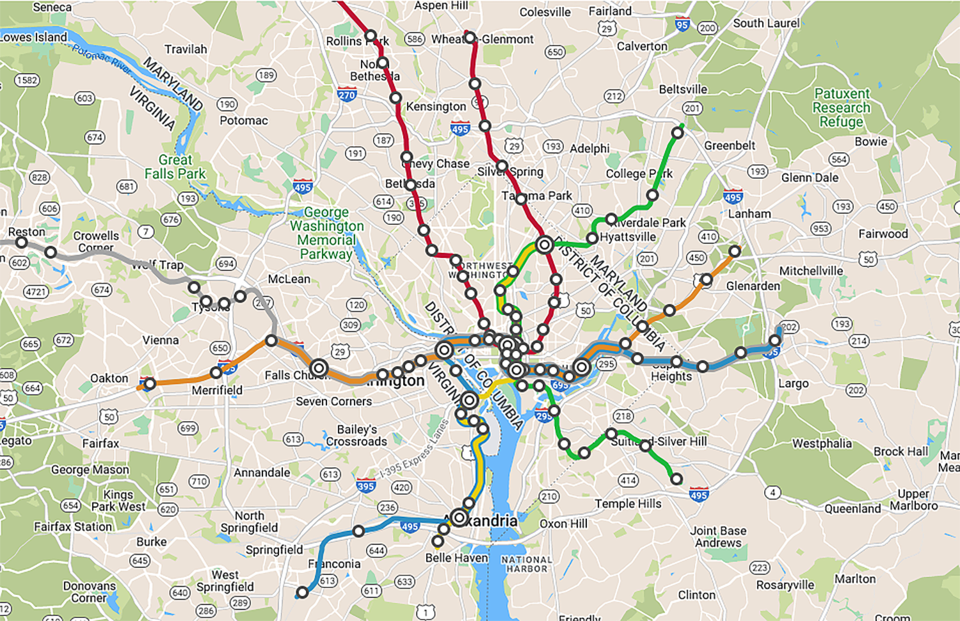

Today, however, with the exception of Prince William County, virtually the entire Washington region is served by Metro and nearly all the elected officials in the region believe in its importance.

But that doesn’t mean they have the interest in writing a perpetual blank check.

“We’re getting to be between a rock and a hard place. We’ve got to do things differently,” County Board member Libby Garvey said.